Sea Turtle or Marine Turtle

Sea turtles are one of the oldest reptilian groups; their lineage predates the dinosaurs. It’s a creature that has roamed the earth’s oceans for more than 100 million years.

According to the researchers, there are seven distinct sea turtle species divided into six genera. Each sea turtle has a common name as well as a scientific name. The popular name often describes a physical trait of the turtle, while the scientific name designates the genus and species.

The preferred foods for sea turtle species vary. And each species of sea turtle uses distinctly diverse habitats for eating, sleeping, mating, and swimming. Even though their environments may overlap, there has been a distinct predilection among different species.

Sea turtles harbor a wealth of ecological significance. But human activities, pollution, climate change, habitat destruction, and overexploitation are threatening their existence.

In today’s journey, we will dive into this remarkable creature’s life cycle, adaptation, and the challenges they’re facing, along with many more. And what can you do to help them? So, let’s get going.

Overview of The Sea Turtle

| Common Name: | Sea Turtle or Marine Turtle |

| Scientific Name: | Superfamily Chelonioidea |

| Kingdom: | Animalia (animals) |

| Phylum: | Chordata (chordates) |

| Class: | Reptilia (reptiles) |

| Family: | Cheloniidae or Dermochelyidae (specific family depending on the species) |

| Order: | Testudines (turtles) |

| Genus: | Various genera based on the species (e.g., Chelonia, Caretta, Eretmochelys, Lepidochelys, Dermochelys) |

| Species: | Specific species within the respective (7 Known) |

| Genera: | Varies according to species (e.g., Chelonia mydas, Caretta caretta, Eretmochelys imbricata, Lepidochelys kempii, Lepidochelys olivacea, Dermochelys coriacea) |

| Diet: | Mostly Omnivore |

| Usual Length: | 2-8 Feet Long (24 – 96 inches” or “60 -244 centimeters”). |

| Weight: | 70 – 1500 Pounds (31 – 681 kilograms”). |

| Lifespan: | 50-100 Years |

Sea turtles, enchanting creatures of the ocean, belong to the “superfamily Chelonioidea” and are reptiles within the order “Testudines” and suborder “Cryptodira.“

They are part of the reptilian class known as Reptilia, which includes turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes), and rhynchocephalians (tuatara).

Chapter 01

Types of Sea Turtles

There are seven known species of sea turtles that descend from this lengthy and ancient lineage. Here’s the list of them:

- Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas)

- Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

- Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta)

- Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

- Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea)

- Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

- Flatback sea turtle (Natator depressus)

The Flatback, Green, Hawksbill, Loggerhead, Kemp’s Ridley, Olive Ridley (all from the family Cheloniidae), and Leatherback (the only member of the family Dermochelyidae) sea turtles.

Both families have a strong affinity for the water, and the majority of the species only show up on coastal beaches to lay their eggs; however, the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) may sometimes be seen to bask inland areas.

Although youngsters of both families naturally prefer temperate regions, adult sea turtles are mostly found in tropical and subtropical waters.

These species all have distinctive characteristics and adaptations that enable them to flourish in various marine habitats.

And all seven species – with the exception of the Flatback – can be found in American waters, but their range goes well beyond our borders.

However, the flatback sea turtle is unique to the waters off of Australia, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia and stands apart with its distinct characteristics and distribution.

The Endangered Species Act lists the majority of sea turtle species as vulnerable, endangered, or both due to the tremendous threats and conservation challenges they confront.

| Species | Scientific Name | Conservation Status | Habitat | Diet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flatback | Natator depressus | Data Deficient | Northern Australia | Invertebrates, sea cucumbers, soft corals |

| Green | Chelonia mydas | Endangered | Tropical and Subtropical Regions | Seagrass, algae, jellyfish, sponges, and more |

| Hawksbill | Eretmochelys imbricata | Critically Endangered | Tropical Coral Reefs | Sponges, algae, soft corals |

| Leatherback | Dermochelys coriacea | Vulnerable | Global Distribution | Jellyfish, salps, tunicates, and more |

| Loggerhead | Caretta caretta | Vulnerable | Temperate and Tropical Waters | Crustaceans, mollusks, fish, and more |

| Kemp’s Ridley | Lepidochelys kempii | Critically Endangered | Gulf of Mexico and Western Atlantic | Crabs, shrimp, jellyfish, and more |

| Olive Ridley | Lepidochelys olivacea | Vulnerable | Tropical and Subtropical Regions | Crabs, shrimp, jellyfish, and more |

Sea turtles can be broadly categorized into two groups based on their shell type: hard-shelled (cheloniid) and leathery-shelled (dermochelyid).

The Leatherback sea turtle, belonging to the dermochelyid family, stands as the sole representative of this unique group.

With its leathery carapace and remarkable adaptations, including a flexible body structure and specialized feeding habits, the Leatherback is a true marvel of evolution.

On the other hand, Cheloniids, known as hard-shelled sea turtles, possess a bony carapace (upper shell) and plastron (lower shell) adorned with epidermal scutes or scales. These scutes provide a protective covering and contribute to the overall rigidity of the turtle’s shell.

Despite being distantly related, Dermochelyids and cheloniids share several amazing characteristics that have allowed them to thrive in their environments. Their evolutionary paths diverged approximately 100-150 million years ago.

Cheloniids have a hard shell with bony architecture and scutes, while dermochelyids have a flexible, leatherback shell without a solid bony structure covered by thick skin.

Chapter 02

Body Description/ Appearances

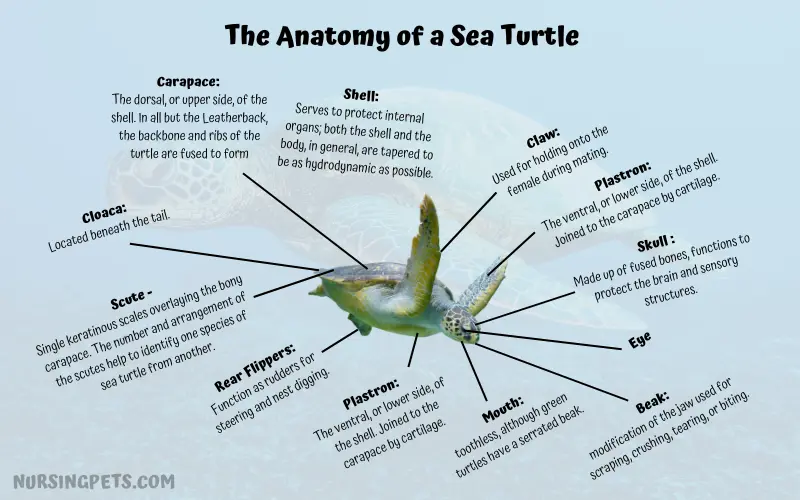

As we hinted, sea turtles have streamlined shells and forelimbs specialized as flippers, which makes it easier for them to move through the water. They have figure-eight swimming strokes for agility in the water and possess large, fully webbed hind feet that function as rudders for precise movements.

Sea turtles have two parts to their shells: a carapace on top and a plastron on the bottom. All but the Leatherback are covered in hard scales or scutes, and the quantity and pattern of these scutes can be used to identify the species.

In addition, sea turtles cannot retract their heads and limbs within their shells for protection like freshwater turtles and tortoises.

And this is because of their tapered body shape at both ends, giving them a more hydrodynamic form. This adaptation minimizes friction and drags in the water, enabling sea turtles to glide effortlessly through their marine habitats.

And the physical description of sea turtles showcases their adaptation to life in the ocean.

Interestingly, sea turtles don’t have teeth. They have mouths and jaws that are uniquely shaped to assist them in consuming the foods they enjoy.

Moreover, sea turtles lack visible ears but possess eardrums concealed beneath their skin. Their auditory perception is most acute when it comes to low frequencies, while their sense of smell is notably keen.

Underwater, they possess good vision, although their focus is nearsighted when on land.

And about claws, sea turtles do possess claws on their flippers. Usually, the front flippers have two claws, while the back flippers normally don’t have any. But the number of claws can vary from species to species.

Sea turtles use their claws to grip or dig. And as for males, their fore flippers claws are curved and elongated, except for the leatherback turtle, which may help them grasp on the female shell during mating.

“We have covered an in-depth article on turtle claws; if interested, you can check this article here.”

Because there is no sexual dimorphism in sea turtles, the size of men and females is often the same.

But the size varies among the seven different species. The Leatherback sea turtle is the largest among all the known seven species. It can reach up to an impressive 2–3 meters (6–9 feet) in length, 1–1.5 meters (3–5 feet) in width, and can be up to a staggering 700 kilograms (1500 pounds) in weight.

| Species | Size (Usual) | Weight (Possible) |

|---|---|---|

| Flatback | 3-4 feet (91 -122 centimeters) | 200 to 220 pounds (90 to 100 kg) |

| Green | 3-4 feet (91 -122 cm) | Up to 700 pounds (318 kg) |

| Hawksbill | 2 – 3 feet (60 – 92 cm) | 100 to 150 pounds (45 to 68 kg) |

| Kemp’s ridley | 2 – 3 feet (60 – 92 cm) | 75 to 100 pounds (34 to 45 kg) |

| Leatherback | 6 – 9 feet (182 -275 cm) | Up to 2,000 pounds (900 kg) |

| Loggerhead | 2 – 3.5 feet (60 – 107 cm) | 200 to 350 pounds (91 to 159 kg) |

| Olive ridley | 2 – 2.6 feet (60 – 80 cm) | 75 to 110 pounds (34 to 50 kg) |

But the other six species aren’t as big as it is. They are comparatively smaller and can range around 2 to 4 feet (60-120 centimeters) in length with proportionally slender or narrower body width.

What is more, examining their unique anatomy, sea turtles possess skulls with cheek regions enclosed in bone, distinguishing them from other reptiles.

While this feature appears similar to the skulls of ancient reptiles known as anapsids, it is likely a more recently evolved trait in sea turtles, placing them outside the anapsid classification.

Chapter 03

Sea Turtles’ Diet

Sea turtles have diverse diets that vary depending on their species. Contrary to popular belief, not all sea turtles solely consume jellyfish.

Their diets play a crucial role in maintaining the health of the ocean and coastal ecosystems by creating a balance in the food web. And different species exhibit different feeding habits.

Loggerhead, Kemp’s ridley, olive ridley, and hawksbill sea turtles are lifelong omnivores. They consume a wide range of plant and animal life, such as decapods, seagrasses, seaweed, sponges, mollusks, cnidarians, echinoderms, worms, and fish.

However, some sea turtle species specialize in certain prey types.

The diet of green sea turtles undergoes a transformation as they age. Juvenile green sea turtles are omnivorous, consuming both plant and animal matter.

But, as they mature, they shift to an exclusive herbivorous diet. This change in diet also influences the morphology of green sea turtles, as they develop a serrated jaw specifically adapted for grazing on sea grass and algae.

Leatherback sea turtles display a unique feeding preference by predominantly consuming jellyfish. Their feeding behavior plays a crucial role in controlling jellyfish populations, which can have significant ecological implications.

Hawksbill sea turtles are known for their principal consumption of sponges, with these marine organisms comprising a substantial portion, ranging from 70% to 95%, of their diet in the Caribbean region.

Now, if we look at the basic diets of each species and break them down individually, this is what sea turtles usually eat and prefer to consume:

Source: Sea Turtle Preservation Society. (n.d.). What Do Sea Turtles Eat

Now, what about drinking? Do sea turtles drink water? Do they need fresh water to survive? How do they adjust the excessive salt in the marine water?

Like other marine reptiles, sea turtles have a unique way of obtaining water and maintaining hydration. They do drink water (salt water), but they primarily obtain their hydration from the food they eat.

As mentioned, sea turtles mainly rely on the moisture present in the food they eat. As you know, their diet consists of various marine plants and animals that naturally provide them with a significant amount of water.

However, after drinking the salt water, to deal with the excess salt content, sea turtles have special glands located near their eyes, known as salt glands or lachrymal glands.

These remarkable glands help them filter out the excess salt, ensuring they maintain a proper salt and water balance in their bodies.

And you might have noticed sea turtles shedding tears while basking on land, and those tears actually contain the concentrated salt that is expelled from their bodies.

Although sea turtles have adapted to survive without relying on regular access to freshwater, they do occasionally seek out estuaries for freshwater (estuaries are areas where freshwater mixes with saltwater, creating a brackish environment).

Visiting these places allows sea turtles to replenish their water balance to some extent. Additionally, sea turtles can also absorb water through their skin while in the ocean, which helps keep them hydrated and provides essential minerals and nutrients.

Chapter 04

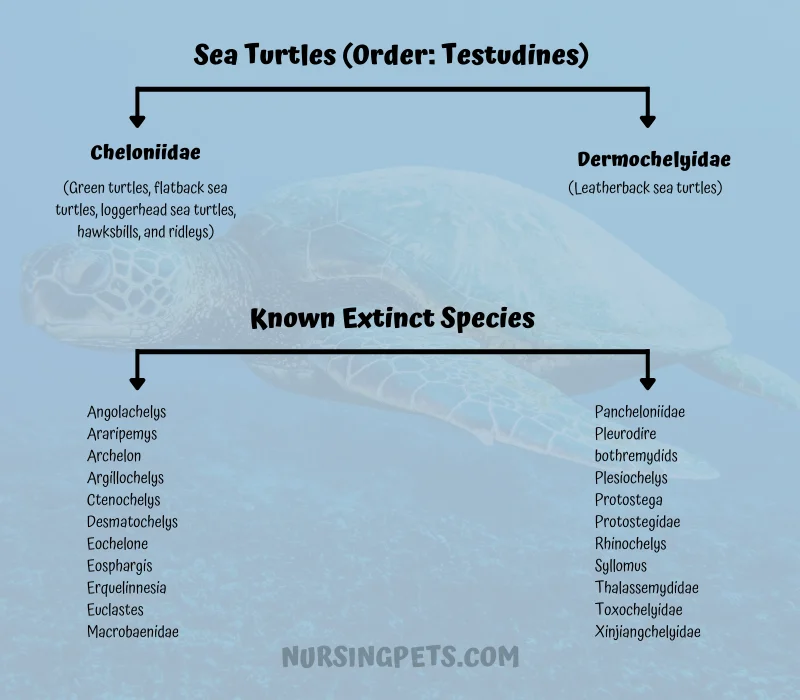

Taxonomy/Order /Family/ Genus of Sea Turtles

Taxonomy provides a systematic framework for classifying and categorizing organisms based on their relationships and shared characteristics. But we won’t go that deep in here, except the basics.

Order

As hinted, sea turtles belong to the kingdom Animalia, the phylum Chordata, and the class Reptilia. They are part of the order Testudines and the suborder Cryptodira.

The order Testudines consists of various species of turtles and tortoises, with sea turtles being a distinctive group known for their adaptation to marine life.

Family

They are further classified into different families based on their specific traits, Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae.

The Dermochelyidae family includes the only member, the leatherback sea turtle with a distinct shell structure. The bones in their shell are comparatively not that strongly connected and are covered with thick, leathery skin.

On the other hand, the Cheloniidae family encompasses several (remaining 6) sea turtle species, such as green turtles, flatback sea turtles, loggerhead sea turtles, hawksbills, and ridleys. These species have a hard-shelled carapace (top shell) and plastron (bottom shell) with epidermal scutes (scales).

Extinct Species

Interestingly, sea turtles have a rich fossil record dating back millions of years. There are some extinct sea turtle species that researchers found, and they have played a significant role in shaping the sea turtles’ evolutionary history. Some well-known extinct sea turtle species are-

- Angolachelys

- Araripemys

- Archelon

- Argillochelys

- Ctenochelys

- Desmatochelys

- Eochelone

- Eosphargis

- Erquelinnesia

- Euclastes

- Macrobaenidae (family)

- Pancheloniidae (clade)

- Pleurodire bothremydids (Both Marine and Freswater)

- Plesiochelys

- Protostega

- Protostegidae (family)

- Rhinochelys

- Syllomus

- Thalassemydidae

- Toxochelyidae

- Xinjiangchelyidae (family)

Please note that “Pelomedusids” and “Pleurodire bothremydids” are not specific genus or family names but rather categories that encompass multiple species within those groups.

Among them, Archelon, which lived during the Late Cretaceous period, holds the distinction of being one of the largest turtles ever recorded. Besides the Pneumatoarthrus, it reigns as a true titan among turtles.

And the largest Archelon specimen was founded and collected from South Dakota.

It was 16 feet from snout to tail and spanning an impressive 13 feet in width from flipper to flipper. The huge skull alone was about 30 inches long. And the probable weight was a staggering 2.2 to 3.2 metric tons (2.4 to 3.5 short tons).

This just shows us a glimpse into the grandeur of prehistoric life. Today, the remains of this magnificent creature can be found at the Naturhistorisches Museum Wien in Vienna, Austria.

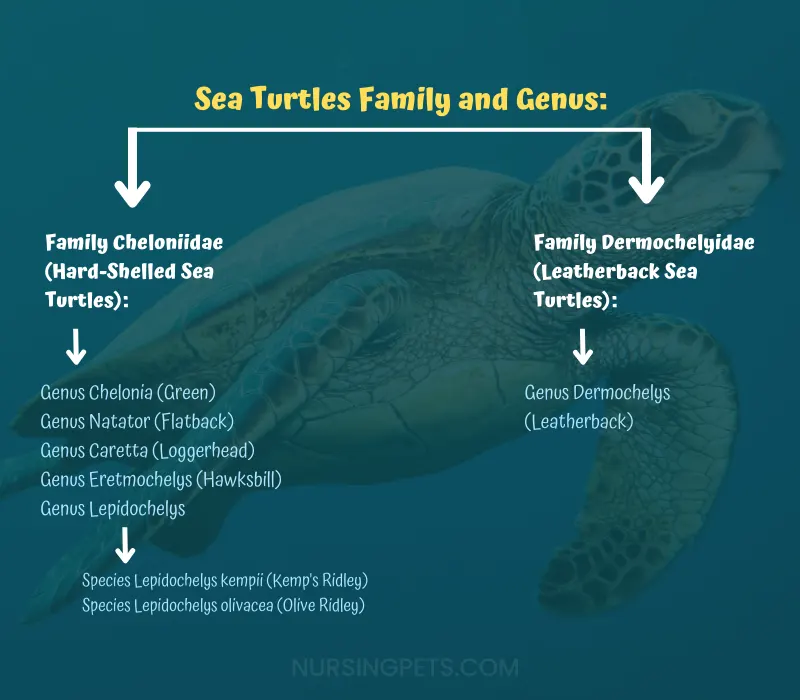

Genus

Within the families Dermochelyidae and Cheloniidae, sea turtles are further classified into different genera. And It is a level of classification below the family.

The classification into different genera allows scientists and researchers to study the unique characteristics, behavior, and ecological roles of each sea turtle species more closely.

In the family Dermochelyidae the leatherback sea turtle, which is the sole extant member of this family, belongs to the genus Dermochelys. It is a unique and distinct species known for its flexible, leathery shell and its ability to dive to impressive depths.

Within the family Cheloniidae, several genera represent the diverse species of sea turtles. These include:

01. Chelonia: The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is a widely recognized sea turtle species known for its herbivorous diet and vibrant green coloration.

02. Natator: Flatback sea turtle (Natator depressus) is a species that inhabits the coastal waters of Australia and is characterized by its relatively flat shell.

03. Caretta: The loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) is a large-bodied species known for its robust head and strong jaws.

04. Eretmochelys: Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is notable for its strikingly patterned shell and critically endangered status.

05. Lepidochelys: The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) and the olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) are both known for their synchronized mass nesting events known as arribadas.

06. Dermochelys: Dermochelys coriacea (Leatherback turtle) consists of scute-less turtles, with the leatherback turtle being the only modern species.

Chapter 05

Population of Sea Turtles

As you can understand, it’s difficult to say exactly how many sea turtles are alive today. Also, counting sea turtles isn’t an easy feat.

Because they often migrate from one place to another for food or nesting. Also, the juvenile and male sea turtles rarely come to the shore. Only the females visit the land to lay eggs.

So, no one can tell the exact number of the turtle population figure of sea turtles. What we have is an estimation based on different survey results and the population trend.

For counting sea turtles population, scientists use different methods. Among them, the most popular and well-known method is counting and observing the annual number of nesting events of the different female sea turtle species.

Because females are the dominant gender, and one research says about 90% of this population is female.

Still, this result isn’t full-proof, and the number of nesting activity does not clearly indicates the adult females in the population.

Why is that? Because sea turtles can lay more than a clutch (total number of eggs laid in one nesting attempt) in a single year, and some do not reproduce every year/season.

And on average, the active reproduction period of sea turtles is about 2-6 years (varies according to different species). Also, they can use the same or different nesting places in a single year.

So, the estimated population numbers are ambiguous and can vary a lot from the original.

However, scientists and researchers try to reduce the error probability percentage by taking several factors into account. When they convert the nesting activity in the population size, they consider- sex ratio, migration pattern and interval, proportion identified and registered number of females, etc.

Despite all of that, a recent publication said, which evaluated this counting process, the current estimated sea turtle population may differ a lot from the existing numbers, and we shouldn’t be too optimistic.

And researchers estimate and believe that around two-thirds (70-90%) of sea turtles’ population have decreased after the beginning of the industrial age in the early 20th century.

So, how many sea turtles are left? According to multiple sources, recent estimations tell us that there are about 6.5 million sea turtles left, with each species’ numbers varying greatly. However, some other sources claim that the current sea turtle population is around only 1 to 1.5 million (unpopular opinion). (source)

Now, when we break down each species and look at the individual nesting population, the number isn’t clear and different sources claim different numbers.

But, if we summarize those and want to have a general estimation/idea, here are the possible existing nesting population of each species of sea turtle; this can give us an idea about the total population:

1. Loggerhead: It is one the most abundant species of sea turtle that nests in the U.S. coastal areas. The estimated nesting population of the loggerhead sea turtle is about 50,000 to slightly over 200,000 around the world. The population has declined by about 60-90% over the last 60 years.

2. Green: The nesting population of green sea turtles is around 60,000 to 90,000. And the largest nesting population of this species was found at Tortuguero of Costa Rica.

3. Hawksbill: This species is marked as a critically endangered species with about 15,000 to 25,000 nesting population. And overall possible population ranges between 55,000- 83,000 only.

4. Kemp’s Ridley: With a population of less than 10,000 population, Kemp’s ridley is abundant in the coastal areas of Mexico.

According to scientists and researchers, there may be only 5,000 to 8,000 left alive today (and another source claim that the medium estimate of this species is about 25,000).

5. Flatback: It is one of the most vulnerable sea turtles that are getting affected by habitat change or exploitation. The possible nesting population of flatback sea turtles is around 20,000 to 30,000. And a medium estimate says that it could be about 69,000 in total.

6. Olive Ridley: Among the seven species, the Olive Ridley is the most prolific sea turtle species, with more than 600,000 to 800,000 female nesting population.

And the total estimated female population is about 2 million. The Pacific coast of Costa Rica alone receives around 500,000 to 600,000 nesting each year.

7. Leatherback: The female nesting population of leatherback sea turtles is around 25,000 – 45,000. And they can be seen in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans (mainly French Guinea, Trinidad, and Suriname). And Scientists believe this species’ population has declined by more than 80%.

| Species | Nesting Population Estimate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Loggerhead | 50,000 to slightly over 200,000 | Population declined 60-90% over the last 60 years |

| Green | 60,000 to 90,000 | Largest nesting population at Tortuguero, Costa Rica |

| Hawksbill | 15,000 to 25,000 | The total possible population is 55,000- 83,000 only. |

| Kemp’s Ridley | Less than 10,000 (estimated) | Estimates range from 5,000 to 8,000 or 25,000 |

| Flatback | 20,000 to 30,000 (possible) | Another estimation suggests a total of about 69,000 only |

| Olive Ridley | More than 600,000 to 800,000 | Most prolific species with a total estimated female population of 2 million |

| Leatherback | 25,000 to 45,000 | Possible population declined by about 80% |

Chapter 06

Distribution and Habitat

Sea turtles inhabit diverse marine environments all around the world. And their natural habitat includes feeding, migration, breeding, and nesting areas.

Most species of these reptiles can be found in the waters over continental shelves, with some exceptions. Sea turtles prefer warm and temperate seas, with different species distributed across various oceans, except for the polar regions.

From shallow coastal waters, bays, lagoons, estuaries, mangrove forests, salt marsh, maritime hammocks, barrier islands, coastal strands, and the beach and dune system to the vast expanse of the open ocean, sea turtles have adapted to a wide range of habitats.

During their early years (3-5 years), sea turtles spend a significant amount of time in the pelagic zone, floating amidst seaweed mats. This is especially true for green sea turtles.

Adult sea turtles are commonly seen in shallow, coastal waters, while some species also venture into deeper oceanic regions. And females often come to the sandy beach areas to lay eggs.

Their habitat preferences vary depending on the species. For example, leatherback sea turtles prefer pelagic (open ocean) environments and the cold waters of Alaska and the European Arctic occasionally, while the flatback sea turtle is exclusive to the northern coast of Australia.

If you’re interested in learning more about sea turtles, you can read this amazing book from Amazon.

Now, if we want to provide a general idea of each sea turtle species’ usual or possible living regions, here’s what it looks like:

Olive Ridley – Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, and India.

Hawksbill – Indo-Pacific Regions, Brazil, Australia, Africa.

Flatback – Papua New Guinea, Australian coasts, and southern Indonesia.

Leatherback – This species has a widespread distribution around the world. Argentina, the Gulf of Alaska, South Africa, California (USA), Tasmania, and India are common.

Green – Atlantic Ocean, Puerto Rico, Mediterranean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Northern Australia, Argentine, African coasts, Pacific Ocean.

Loggerhead – Usually, this species can be found in coastal bays and streams of all continents except Antarctica.

Kemp’s Ridley – Gulf of Mexico, South part of USA, and a few of them can be found in the Mediterranean Sea and Morocco.

Chapter 07

Migration

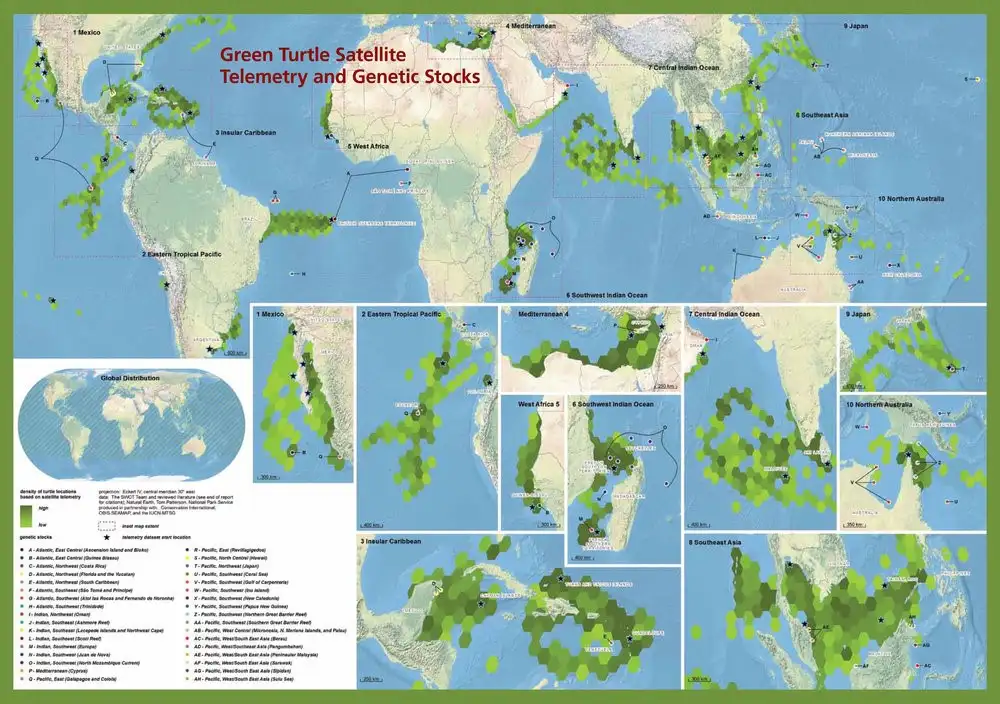

Sea turtle migration is a long-distance movement, especially of the adults, between their nesting sites and foraging grounds, and often seasonally move to the warmer areas of the seas. Also, the offshore migration of hatchings.

It can be hundreds to thousands of miles. Some claim that sea turtles can migrate up to 10,000 miles in a single year.

Although it is hard to keep track of their migration behavior, thanks to advancements in satellite telemetry, scientists now have the means to observe the movements of sea turtles with unprecedented precision.

The migration pattern varies among different species and even in the same species or in the population.

While the exact navigational mechanisms of sea turtles remain a mystery, researchers believe that cues such as ocean currents, the earth’s magnetic field, water chemistry, and other environmental cues contribute to their ability to find their natal beaches.

For a better understanding, let’s break down the total sea turtle migration into different categories. So we can realize the matter more clearly.

Nesting and Breeding Migration

Sea turtles, both males and females, undertake migrations to reach their breeding beaches, often returning to the same area where they were born. For nesting, they prefer tropical and subtropical regions worldwide,

Hatchling Migration

Sea turtle hatchlings emerge from their underground nests and embark on a critical journey to the safety of the ocean. Within the first 48 hours, they must navigate from the beach to a location where they are less vulnerable to predators and can find food.

Many hatchlings in the Atlantic and Caribbean regions are carried by Gulf Stream currents, which often transport them to areas abundant in floating sargassum weed.

These nutrient-rich regions provide ample food and protection from predators. After several years of floating in the Atlantic, young turtles venture back into nearshore waters.

Juvenile Feeding and Adult Migration

During their juvenile years, sea turtles primarily inhabit nearshore habitats, feeding and growing. However, as they reach adulthood and sexual maturity, it is believed that they migrate to new feeding grounds.

These primary feeding areas likely become their long-term habitats, with occasional departures during the breeding season. The distance between feeding and nesting sites can be extensive, requiring some turtles to migrate hundreds or even thousands of kilometers throughout their lives.

Species-Specific Migration Patterns

As mentioned, adult sea turtles exhibit various migration patterns, each unique to different species. Among them, several key migration patterns have been identified.

For instance, green sea turtles engage in a shuttle-like movement between nesting sites and coastal foraging areas.

Loggerhead sea turtles, on the other hand, utilize a series of foraging sites along their migration routes. While loggerhead sea turtles have a widespread distribution and can be found in various oceanic regions, their nesting sites are primarily located in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

In the Atlantic, loggerhead sea turtles nest along the coasts of Florida, the southeastern United States, the Caribbean, and other locations in the region. In the Indian Ocean, they nest in areas such as Oman, Greece, Turkey, and Australia.

They can undertake an impressive migration of nearly 8,000 miles from different locations to the rich waters off Baja, California, and Mexico, where they feed and mature.

In contrast, leatherback and olive ridley sea turtles do not demonstrate a strong preference for specific coastal foraging sites. Instead, they roam the open seas, engaging in intricate movements seemingly without a defined destination.

While leatherbacks’ foraging movements are largely influenced by passive drift with ocean currents, foraging jellyfish can lead them to different areas. And they possess the astonishing ability to return to specific locations for breeding purposes.

Interestingly, among the most highly migratory animals, leatherbacks travel up to 10,000 miles annually. In the Atlantic, they journey from Caribbean beaches up the US East Coast to Canada. In the Pacific, they migrate from Southeast Asia to California and even Alaskan waters.

The flatback turtle stands out among its sea turtle counterparts as the only species that does not venture to the Americas. It mostly inhabits the coastal waters of Australia and Papua New Guinea and those regions.

And compared to other sea turtles, the flatback turtle undertakes shorter migrations, covering less distance. This unique species is recognized for its nesting activities along the beaches of Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and Queensland.

The last one, Hawksbill, is one highly migratory animal; it can travel between 800 to 1,650 kilometers for nesting and foraging foods.

But the migration routes and patterns of hawksbill sea turtles can vary among individuals, and they often exhibit circuitous routes even for short distances, indicating that their navigational sense in the open ocean is relatively crude.

Navigation Mechanisms of Sea Turtles

The navigational abilities of sea turtles continue to intrigue scientists. While the exact methods they employ remain unclear, it is suggested that turtles might use the Earth’s magnetic field as a navigational compass during long migrations.

Evidence supporting this hypothesis exists, particularly in juvenile green sea turtles. Other potential navigational cues, such as astronomical cues from the sun, moon, and stars, have not been firmly supported by scientific evidence.

Also, sea turtles have a remarkable homing instinct, which enables them to navigate vast distances to reach their breeding grounds.

Technological Advances in Tracking

Historically, researchers relied on flipper tags and sightings to gather information on sea turtle migration. However, recent advances in radio and satellite tracking have revolutionized the monitoring of sea turtle movements.

Tools like radio/satellite transmitters, developed by institutions like the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute, provide secure attachment and facilitate the collection of detailed data on migration routes.

Chapter 08

Mating-Reproduction and Nesting Behavior

Reproductive behaviors and timing may differ across sea turtle populations and species, but there is a common pattern observed among all sea turtles. However, all of the species are egg layers. And they use sandy beach areas for nesting.

Sexual Maturity

The age at which sea turtles reach sexual maturity varies among species. It can range from as early as 3-5 years, while some may reach sexual maturity around 40-50 years. And remain productive for 10-19 years.

Well, the below table will give you a general idea of the average ages at which different species of sea turtles reach their sexual maturity.

| Sea Turtle Species | Maturity Range (in years) |

|---|---|

| Leatherback | 7 – 13 |

| Ridley (both species) | 11 – 16 |

| Hawksbill | 20 – 25 |

| Loggerhead | 25 – 35 |

| Green | 26 – 40 |

| Flatback | 7-25 |

## Please note that these maturity ranges are approximate and can vary based on various factors, such as environmental conditions and individual variations within the species.

According to some sources, sexual maturity in sea turtles is closely linked to the size of their carapace or shell.

Research indicates that hawksbills typically reach maturity when their carapace size measures between 69 and 78 cm (27 to 31 inches). For loggerhead turtles, sexual maturity is achieved at a carapace size ranging from approximately 50 to 87 cm (20 to 34 inches).

As for leatherbacks, these majestic creatures attain sexual maturity when their carapace size reaches a considerable 145 to 160 cm (57 to 63 inches).

However, some turtles may stop growing after reaching sexual maturity, and some may grow further after that.

Mating Activity

Courtship and mating for sea turtles occur during a limited “receptive” period before the female’s first nesting emergence. Males may court females by nuzzling their heads or gently biting their necks and rear flippers.

And copulation can take place on the surface or underwater. Females may mate with several males and store their sperm for a few months.

Nesting Season

The nesting season for sea turtles generally occurs from May to September. However, the timing may vary depending on the species. Leatherback turtles, for example, nest in fall and winter.

Nesting Frequency

Females may lay between 1 and 9 clutches of eggs per nesting season. They usually nest every 2 or 3 years.

Nesting Site Selection

Females usually return to the same beach where they hatched to nest each year. Beach selection seems to be a faithful behavior for sea turtles. And most female turtles come back to their birthplace for nesting and laying eggs.

Nesting

Female sea turtles return to the beaches where they were hatched to lay their eggs. They come ashore, usually at night, and dig a nest using their hind flippers. The depth of the nest can be up to 1 meter deep.

The female deposits 50 to 300 eggs, depending on the species, into the nest and covers it with sand. The eggs are soft-shelled, ping-pong ball-shaped, and surrounded by thick, clear mucus.

| Sea Turtle Species | Clutch Size Range (Possible Number of Eggs Per Clutch) |

|---|---|

| Green Turtle | 110 |

| (Black Subspecies) | 65 – 90 |

| Olive Ridley | 110 |

| Kemp’s Ridley | 110 |

| Hawksbill | 130 |

| Loggerhead | 122 |

| Flatback | 54 |

| Leatherback | 50 – 100 |

Sex Determination

Interestingly, the temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchlings. Cooler sand produces more males, while warmer sand produces more females. This temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) phenomenon is believed to be true for most sea turtle species.

Incubation and Hatching

The eggs incubate in the warm sand for about 60 days. When the hatchlings are ready to emerge, they do so in unison, creating a scene known as a “turtle boil.” They race to the ocean, guided by the downward slope of the beach and the reflections of the moon and stars on the water.

Hatching and moving together helps them overwhelm waiting for predators. The survival rate of hatchlings is low, and only about 10% of them reach adulthood.

Chapter 09

Life Span and Life Cycle

The lifespan of sea turtles varies from one species to another, and different environmental factors play a role here. On average, sea turtles live around 50-100 years. And among the seven, small species live about 30-80 years, while the larger ones can easily live for 100 years or more.

However, scientists aren’t sure about the exact lifespan of sea turtle species because there is no proven method for determining the age of sea turtles.

Skeletochronology is the only scientific method for finding a sea turtle’s nearly exact age. Unfortunately, this test can only be performed on a dead sea turtle. And an average person can’t perform this test.

This method involves the histological analysis of skeletal growth marks in the turtle’s bones. These growth marks, similar to tree rings, can provide valuable information about the turtle’s age and growth rate.

Other than skeletochronology, the visual signs, the size of the carapace, and comparison with other sea turtles can give you an idea about their age. But none of these methods are genuine or accurate.

Over the past few decades, there have been some striking cases where sea turtles have surpassed these estimated lifespans.

For instance, back in 2006, Li Chengtang, who served as the head of the Guangzhou Aquarium in China, revealed an intriguing discovery.

At that time, the aquarium housed a sea turtle that was believed to be around 400 years old (the oldest sea turtle found in recent times), as determined through a shell test conducted by a taxonomic professor. However, the sources of this information aren’t strong.

Similarly, another fascinating account emerged from the Philippines, where an elderly sea turtle made headlines. According to a news report, a sea turtle nearing the age of 200 was found in a fish pen and subsequently transferred to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources.

| Sea Turtle Species | Average Lifespan (in Years) | Maximum Lifespan |

|---|---|---|

| Green Turtle | 70 – 90 | + 100 years |

| Loggerhead | 50 – 80 | + 90 Years |

| Hawksbill | 40 – 60 | + 100 years |

| Kemp’s Ridley | 30 – 60 | + 60 years |

| Olive Ridley | 30 – 60 | + 60 years |

| Leatherback Turtle | 45 – 90 | Unknown |

| Flatback | 40 – 80 | + 100 Years |

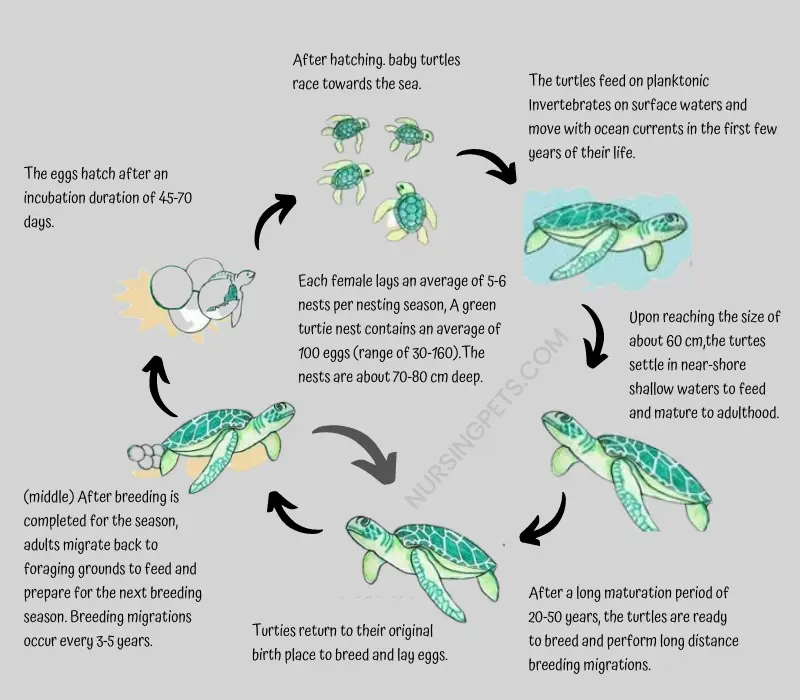

Sea turtles lead an extraordinary life cycle, filled with remarkable events and challenges from the moment they hatch to their eventual passing.

It all begins with the arrival of a female sea turtle onto the sandy shores, where she carefully selects a nesting spot to lay her eggs. Most of the time, sea turtles come in groups, also known as “arribada.”

Each turtle digs a deep hole and gently deposits her clutch of eggs, delicately covering them with sand to ensure their safety.

With the duty of incubation complete, the female returns to the ocean, leaving the future of her offspring in the hands of nature.

The eggs remain nestled in the warmth of the sand. Interestingly, the temperature of the nest determines the gender of these future turtles.

After several weeks or months, the hatchlings start to emerge. After that, these tiny, vulnerable creatures instinctively try to reach the ocean.

Not all of them can make it to the end; some lose their way, and some become the prey. Even in the water, only a small percentage of them survive to reach maturity because of numerous challenges and predators.

Once immersed in the ocean, the hatchlings drift along the currents and spend their early years navigating the open ocean, feeding on plankton and other small invertebrates that help them during this transient phase, which is also known as the “lost years.”

As they grow in size and strength, sea turtles venture closer to coastal areas, undergoing an astounding transformation from tiny hatchlings to juvenile turtles.

In this phase, they adapt to a diet that sustains their growth, embracing seagrass, algae, and small marine creatures. Here, they have to survive from pollution, fishing gear, habitat degradation, and the impacts of climate change.

Depending on the species, juvenile turtles take a few to several years to their adulthood. And adult sea turtles usually return to their native areas to reproduce.

Once there, they engage in mating. Males often compete with others for mating partners, and a single female can copulate with multiple males. Then, female sea turtles prepare for nesting. And the cycle goes on.

Chapter 10

Sea Turtle Behavior

The activity or behavior of sea turtles is still a mystery to the enthusiasts. Very little is known to us. But if we break it part by part, it may help us to have a general grasp of the matter.

Daily Activities

Sea turtles are known to feed and rest off and on during a typical day. Feeding is a crucial part of a sea turtle’s daily routine. The specific diet of a sea turtle depends on its species.

And they may rest at the water’s surface, occasionally popping their heads out to breathe or seek sheltered areas such as reefs and rocks for rest. However, during the migration, sea turtles navigate through the ocean to reach their desired destinations.

Feeding Behavior

Marine turtles can be one of three types- carnivore, herbivores, or omnivores. And these are:

Carnivorous: Some species of sea turtles eat mostly meat as their main source of food. Their usual preys are- jellyfish, crustaceans, mollusks, and small marine mammals.

Herbivorous: This type mainly eats ocean vegetation like seagrass and algae. Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are an example of herbivorous sea turtles. Their finely serrated jaws adapted for a mostly vegetarian diet.

As adults, they are primarily herbivorous, but occasionally they may also consume jellyfish and sponges. However, No species of sea turtles aren’t fully herbivorous.

Omnivorous: Most sea turtles are omnivores, eating both meat and plants. Loggerhead, Flatback, and olive ridley are well-known in this category. Their diet includes a variety of prey items such as jellyfish, crustaceans, mollusks, fish, and vegetation.

Social Behavior

Sea turtles are not generally considered social animals, but some species do congregate offshore. They gather together to mate, and members of certain species may travel together to nesting grounds.

However, after hatchlings reach the water, they typically remain solitary until they mate.

Individual Behavior

Little is known about the individual behavior of sea turtle species. However, observations have revealed some interesting behaviors. For example, flatback turtles may spend hours at the surface floating, appearing to be asleep or basking in the sun.

Among seven species, Hawksbill turtles are known to spend time resting or sleeping wedged into coral or rock ledges. Olive ridleys have been observed basking on beaches, and it is not uncommon to see thousands of olive ridleys floating in front of the nesting beach.

Sleeping and Basking

Sea turtles exhibit different behaviors related to sleeping and basking. Some species, like flatback turtles, may appear to sleep or bask in the sun at the ocean’s surface for extended periods. Seabirds can often be seen perching on the backs of flatback turtles.

Hawksbill turtles, on the other hand, may rest or sleep wedged into coral or rock ledges. Olive ridleys have also been observed basking on beaches.

Mating Behavior

Males do not establish a social hierarchy or ranking among themselves. Instead, multiple males can mate with a single female, and the female decides which male she chooses to mate without any inherent status order. And as mentioned, females can mate with multiple males in a single season.

Nesting Behavior

Nesting is a significant behavior unique to female sea turtles. After reaching maturity, female sea turtles return to land to lay their eggs. They emerge from the water and carefully select nesting sites on specific beaches.

Female sea turtles dig nests in the sand using their flippers, lay their eggs, cover the nest, and then return to the ocean.

Nesting typically occurs at night to reduce the risk of predation. This behavior ensures the continuation of their species by providing a safe environment for the development of their offspring.

Migration Behavior

During their migrations, sea turtles primarily focus on reaching their desired destinations, such as nesting or foraging grounds. They maintain a determined offshore heading, often following ocean currents and utilizing cues like the Earth’s magnetic field and water chemistry for navigation.

The exact routes and distances traveled may vary depending on the species and populations.

Feeding habits during migration also vary among different species. However, during migration, sea turtles generally do not feed extensively as their primary focus is reaching their intended location.

Sea turtles may exhibit both solitary and social behaviors during migration. Some species, like the loggerhead turtles, tend to migrate alone.

However, in certain instances, sea turtles may aggregate in groups during migration, especially when they encounter favorable feeding areas or when converging at nesting sites.

Sea Turtle Waste Elimination: How Sea Turtles Pee and Poop?

Sea turtles have their own unique way of excreting waste. Like other animals, they have to relieve urine and feces from their bodies.

When it comes to peeing, sea turtles don’t have a separate bodily function for it as humans do. They do not possess a bladder to store liquid waste like urine. Instead, they excrete urine through the “cloaca,” a multipurpose opening.

This cloaca serves various functions, including reproduction, egg-laying, and waste elimination. So, in a sense, you could say that sea turtles release their urine through their “backdoor” or cloaca.

Now, let’s talk about their pooping behavior. Sea turtles, being aquatic creatures, have to find a way to eliminate their feces while submerged in water. They have two main methods for this.

One way is by floating on the water’s surface and letting their feces be released into the surrounding water. The other method involves descending to the ocean floor and depositing their feces there.

The specific method used depends on the species of turtle and the situation at hand. For example, loggerhead turtles usually poop on the surface, while green turtles may choose to deposit their feces on the seafloor.

Chapter 11

Sea Turtle’s Physiology (Physical Adaptation for Marine Environment)

The ocean is a vast and challenging environment, and within its depths, sea turtles have evolved extraordinary physiological adaptations that enable them to thrive in this aqueous realm.

Shell: A Remarkable Protective Shield

Sea turtle’s shell is one of the distinctive features of this reptile. It has two parts- the carapace (dorsal/back shell) and the patron (ventral/frontal shell). The shell serves a crucial purpose, offering both protection and support to their delicate internal organs.

As you may know, their shell is made of a series of bony plates that are coated with a layer of keratin (a material found in human nails). The shell is both strong and resilient.

Body Shape: Adapted for Aquatic Mastery

Sea turtles possess a body shape that perfectly suits their life in the vast ocean. Their streamlined physique allows them to glide effortlessly through the water. To aid in their aquatic propulsion, their limbs have undergone an amazing transformation, evolving into flippers.

While both front and rear flippers contribute to their swimming ability, the front flippers are larger and more robust, enabling precise steering and powerful forward motion.

Respiration and Diving into the Water

Sea turtles, being reptiles, have lungs and breathe air rather than extracting oxygen from the water as fish do through their gills. When sea turtles are in the water, they hold their breath and rely on the oxygen stored in their lungs.

They have adapted to stay submerged for extended periods of time by slowing down their heart rate and reducing their oxygen consumption. This allows them to conserve oxygen and stay underwater for several hours, depending on the species and activity level.

According to researchers, marine turtles are one of the longest and deepest diving air-breathing vertebrates. In fact, these animals spend less than 10% of their time at the sea surface.

When under the water and active, sea turtles can keep their breathing for several minutes (about 20-40 minutes or so).

But if they are resting or sleeping, they can hold their breath for 80-120 minutes (some claim 4-7 hours, and it varies depending on the species) before resurfacing to replenish their oxygen supply.

And the diving depth of sea turtles varies among species. Leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the largest species of sea turtles, are capable of diving to remarkable depths.

According to the Olive Ridley Project, leatherbacks can dive to depths of more than 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) in search of their primary prey, jellyfish. Other species of sea turtles generally dive at shallower depths compared to leatherbacks.

Hard-shelled species, such as green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), typically dive up to around 175 meters (500 feet), with olive ridleys (Lepidochelys olivacea) recorded at over 200 meters (660 feet). The specific depth capability may vary within individuals and populations.

Sea turtles’ unique adaptations, such as a flexible breastbone and a leathery shell that absorbs nitrogen, help reduce the risks associated with deep dives and resurfacing, such as decompression sickness or “the bends.”

They have a higher concentration of blood pigments, such as hemoglobin, which can carry and release oxygen effectively. Marine turtles also have a larger blood volume and greater oxygen-carrying capacity, enabling them to sustain longer dives.

Moreover, sea turtles exhibit bradycardia, a decrease in heart rate, during dives to conserve oxygen.

Sea Turtle’s Vision

Sea turtles have sharp vision both in water and on land. Their eyes are well-equipped for underwater sight, with clear lenses and a large number of color receptors called cones, allowing them to see a wide range of colors.

Under the water, sea turtles can see clearly in different lighting conditions. They have a special layer behind their retinas called the tapetum lucidum, which enhances their vision in low-light environments by reflecting light back through their retinas.

This adaptation lets them see well, even in the darker depths of the ocean. Sea turtles also have color vision, which helps them distinguish between various hues and shades. This ability comes in handy when locating food, identifying potential mates, and familiarizing themselves with their environment.

They are also sensitive to polarized light, which refers to light that vibrates in a specific plane. By detecting subtle differences in the polarization patterns of light bouncing off the water’s surface, sea turtles can navigate and orient themselves.

To find their way during long-distance migrations and return to their nesting beaches, sea turtles rely on visual cues. They take note of the sun’s position, the Earth’s magnetic field, and the patterns of polarized light to guide them.

Some sea turtle species, like loggerhead turtles, have exceptional night vision. They can see in dim lighting conditions and often use celestial cues, such as the moon and stars, to navigate during their nocturnal activities.

Digestive System

Sea turtles have specialized digestive systems that enable them to process and extract nutrients from their food. Some important aspects of their digestive system are:

Mouth and Esophagus: Sea turtles capture and manipulate their food using their strong jaws and beaks. The food passes through the esophagus, a tube-like structure that connects the mouth to the stomach.

Stomach: They have a relatively simple stomach that performs limited digestion. It secretes digestive enzymes to break down the food further.

Intestine: Most of the digestion and nutrient absorption takes place in the small intestine of sea turtles. The intestine is relatively short but coiled, increasing the surface area for absorption. It is here that the majority of bacterial activity occurs.

Cloaca: Sea turtles have a cloaca, a chamber where the digestive and reproductive systems meet. Waste products, including undigested food, are expelled through the cloaca.

Gut Microbiota: Recent studies have indicated that sea turtles harbor specialized gut microbiota that aids in the breakdown of complex carbohydrates and the fermentation of plant materials.

Osmoregulation (Salt Gland)

Sea turtles maintain an internal environment that is hypotonic (lower salt concentration) compared to the ocean. They excrete excess salt ions through a specialized gland called the lachrymal gland, which produces tears with a higher salt concentration than seawater.

Leatherback sea turtles, whose primary prey is jellyfish and other gelatinous plankton with the same salt concentration as seawater, have a larger lachrymal gland to cope with the higher intake of salts.

Thermoregulation

Sea turtles are poikilotherms, meaning their body temperature is dependent on the surrounding environment. However, leatherback sea turtles can maintain a body temperature of 8 °C (14 °F) warmer than the ambient water through gigantothermy.

This trait allows them to maintain a body temperature that is significantly higher than the ambient water temperature. Gigantothermy is achieved through various physiological adaptations, such as a large body size, a thick layer of insulating fat, and countercurrent heat exchange mechanisms.

On the other hand, some sea turtles may bask in the sun to maintain their body temperature. For example, Green sea turtles in cooler regions exhibit thermoregulatory behavior by hauling themselves out of the water onto remote islands to bask in the sun.

Fluorescence

Sea turtles are the first biofluorescent reptiles found in the wild. Fluorescence has been observed in various marine creatures, and it is believed to serve purposes such as attracting prey, communication, defense, and camouflage.

Observations of biofluorescence in sea turtles were made during a night dive of Gruber and Sparks (2015), and it is best observed with a blue LED light and an orange optical filter.

Sensory Modalities – Navigation

Sea turtles undertake significant migrations to nesting or foraging grounds, sometimes crossing entire ocean basins. They possess a bicoordinate magnetic map and magnetic compass sense for navigation, termed Magnetoreception.

These magnetic senses help them determine their position relative to a goal, maintain a specific magnetic heading, and navigate within strong gyre currents. Natal homing behavior, where sea turtles return to their natal beaches to nest, is influenced by magnetic fields.

The exact mechanisms of natal site learning, including the role of magnetic information, socially facilitated migration, and geomagnetic imprinting, are still being studied.

Chapter 12

Threats and Predators to Sea Turtles

As you may know, sea turtles play a crucial role in our marine environment. But their existence or survival is becoming a challenge day by day. From natural predators to human-made threats, these reptiles encounter various dangers that jeopardize their natural life cycle.

Sea Turtle Predators

Sea turtles have several natural predators at different stages of their lives. Here are some of the predators mentioned in the provided information:

Predators of Sea Turtle Eggs and Hatchlings: Sea turtle eggs and hatchlings are particularly vulnerable to predation. According to some sources, more than 90% of hatchlings are eaten by predators. Some of their predators include:

Predators of Young Sea Turtles: Once the hatchlings make their way to the water, they face additional predators, including:

Predators of Adult Sea Turtles: Adult sea turtles have fewer predators due to their large bodies and hard shells. However, they are still vulnerable to:

Please note that the specific predators can vary depending on the location and species of sea turtle.

Threats to Sea Turtles

Sea turtles face numerous threats that impact their survival and population numbers.

Here are some of the major threats to sea turtles:

Habitat Loss: Destruction and alteration of nesting beaches, feeding grounds, and migration routes due to coastal development, pollution, erosion, dune systems, feeding habitats for sea turtles, and climate change impact the availability and quality of essential habitats for sea turtles.

Sea Pollution (Debris): Marine pollution, including plastic debris, oil spills, and chemical contaminants, can harm sea turtles through ingestion, entanglement, or direct exposure, leading to injuries, diseases, and even death.

Sea turtles are often seen to eat plastic, and they do this mistakenly, confusing it with their regular diet or natural component. And the ingestion of plastic can create blockages in their digestive system and lead to internal bleeding, ultimately resulting in their death.

Climate Change Effects on Nesting: Rising temperatures can disrupt the natural balance of sea turtle populations. Warmer incubation temperatures can result in a higher proportion of female hatchlings, affecting their reproductive success and potentially leading to skewed sex ratios.

Artificial Lighting: Coastal lighting can disorient hatchlings, causing them to move away from the ocean and towards danger instead of following the natural moonlight to find their way. Artificial lighting near nesting beaches can also deter females from coming ashore to nest.

Poaching and Illegal Trade: Illegal trade and consumption of sea turtle’s eggs and meat are becoming a great concern, especially in countries like China, the Philippines, India, Indonesia, and the coastal nations of Latin America. Sadly, it is estimated that Mexico and Nicaragua together kill up to 35,000 sea turtles annually.

Also, sea turtles’ shells and other parts of their body have high demand in the black market for decoration and are believed to have health benefits.

Bycatch: Often sea turtles unintentionally get caught in fishing gear, such as nets, lines, and traps. This bycatch can cause injuries, drowning, or death for turtles, particularly in industrial fishing operations.

Noise Pollution: Underwater noise pollution from human activities, including shipping, construction, and seismic surveys, can disrupt sea turtles’ communication, feeding patterns, navigation, and breeding behavior. And these activities can harm the sea turtle.

Disease and Parasites: Sea turtles are also vulnerable to different diseases, viral infections, and parasites. These can weaken their immune system and overall health condition. And some of the usual ones are- fibropapillomatosis (FP).

It causes the development of unsightly external and internal tumors in sea turtles and primarily affects loggerheads and green sea turtles.

Other than that, they can get affected by herpesvirus and internal/external parasites.

Barnacles: Barnacles on sea turtles are more like a nuisance than a direct threat. They can create drag in the water, making swimming more difficult for turtles. Also, barnacles can cause skin irritations and have the potential to cause infections.

However, the impact varies depending on the severity of the infestation and the turtle’s overall health.

Chapter 13

Human-Turtle Relationship (Human Impact on Sea Turtles)

Throughout history, humans have shared a complex and intricate relationship with sea turtles. This connection has been characterized by a mixture of exploitation and conservation efforts, shaping the fate of these remarkable creatures.

Sea turtles have long been targeted worldwide, despite many countries enacting laws against hunting them. Unfortunately, these marines continue to be harvested for food, with some cultures considering them a delicacy.

In the 1700s, sea turtles were even consumed as a luxurious treat in England, pushing them dangerously close to extinction. Ancient Chinese texts from the 5th century B.C.E. also describe sea turtles as exotic delicacies.

Coastal communities heavily rely on sea turtles as a source of protein, often capturing several at once and keeping them alive until needed. Additionally, sea turtle eggs are gathered for consumption too.

To a lesser extent, certain species are targeted for their shells. The hawksbill sea turtle, in particular, is sought after for its carapace scutes, which are used to create tortoiseshell ornaments such as combs, brushes, and jewelry in Japan and China.

In the past, the ancient Greeks and Romans processed sea turtle scutes, primarily from hawksbill turtles, to craft various elite articles and ornaments like combs and brushes.

And the flippers’ skin is prized for making shoes and other leather goods, while in some West African countries, sea turtles are harvested for traditional medicinal purposes. The allure of these products led to overhunting and pushed sea turtle populations to the brink of extinction.

Thankfully, the tides have turned, and a growing consciousness of the need for conservation has emerged. Today, concerted efforts are being made to protect and preserve sea turtles and their habitats.

Governments, organizations, and communities across the globe are implementing measures to safeguard these magnificent creatures.

And there have been positive shifts in certain coastal towns, like Tortuguero, Costa Rica, where they have transitioned from an industry based on selling sea turtle products to embracing ecotourism. Tortuguero is considered the birthplace of sea turtle conservation.

In the 1960s, the demand for sea turtle meat, shells, and eggs was devastating to the once-thriving sea turtle populations nesting on its beaches.

The Caribbean Conservation Corporation stepped in and collaborated with local communities to promote ecotourism as a sustainable alternative to hunting. This led to the preservation of sea turtle nesting grounds.

Today, Tortuguero attracts numerous tourists who visit the protected 35-kilometer beach to witness sea turtle walks and nesting sites. To minimize disturbance, certified guides accompany visitors on these walks, safeguarding the sea turtles.

This ecotourism initiative has not only created a financial stake for the locals in conservation efforts but has also empowered them to protect the sea turtles from threats such as poaching.

Similar conservation activities are carried out by volunteers in other parts of the world, involving beach patrols, relocating sea turtle eggs to hatcheries, and assisting hatchlings in reaching the ocean.

Examples of such efforts can be found along the east coast of India, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sham Wan in Hong Kong, and the coast of Florida.

Furthermore, volunteers and conservation organizations play a vital role in nurturing the human-turtle relationship. They tirelessly patrol beaches, carefully relocate sea turtle eggs to safe hatcheries, and assist hatchlings on their perilous journey to the ocean.

These dedicated individuals work to minimize the impact of human activities on sea turtle breeding sites, championing the survival of these extraordinary creatures.

Yet, challenges persist. Illegal hunting, unintentional entanglement in fishing gear, pollution (particularly plastic ingestion), and the destruction of critical habitats continue to jeopardize sea turtle populations.

Climate change, with its rising temperatures and sea levels, further exacerbates these risks, threatening nesting grounds and altering hatchling ratios.

Nonetheless, humans are increasingly recognizing the ecological importance of sea turtles and the urgency of their conservation. The human-turtle relationship is evolving, transitioning from a history of exploitation to one defined by appreciation and preservation.

By working together, we can forge a brighter future for sea turtles, ensuring their survival for generations to come.

Therefore, human dedication and intervention are crucial in ensuring the survival of sea turtles, especially in areas where their breeding sites are endangered by human activities.

Chapter 14

Sea Turtles in Different Cultures (Symbolism)

Sea turtles symbolize various meanings and hold significance in different cultures and spiritual practices. Here are the key symbols and meanings associated with sea turtles in different cultures:

1. Native American Culture: In Native American tribes, sea turtles are revered as symbols of Mother Earth, wisdom, and resilience. They are often related to creation myths and represent the enduring spirit of life.

2. Hawaiian Culture: Known as “honu” in Hawaiian, sea turtles have deep symbolism in Hawaiian culture. They are considered sacred and are believed to be the embodiment of ancestral spirits. Sea turtles are associated with good luck, wisdom, and protection.

3. Celtic Culture: In Celtic culture, sea turtles represent longevity, stability, and wisdom. They are associated with the concept of the cosmic turtle, which symbolizes the foundation and order of the universe.

4. Ancient Greek: Sea turtles held significance in ancient Greek mythology. Greeks believed these mariners were with Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, and were believed to symbolize fertility, rebirth, and protection.

5. Ancient Egyptian: Creatio, fertility, and protection; these are symbolic roles of sea turtles in ancient Egyptian culture. They were linked with the goddess Nut, who was often depicted as a turtle.

6. Taoism: Sea turtles have symbolic importance in Taoism, representing longevity, wisdom, and immortality. The image of a turtle with a snake on its back, known as the “Black Tortoise,” is a prominent symbol in Taoist philosophy.

7. Moche: The Moche people of ancient Peru held sea turtles in high regard, often featuring them in their art. J. R. R. Tolkien’s poem “Fastitocalon” reflects a second-century Latin tale from the Physiologus.

It describes the Aspidochelone, an enormous turtle that lures sailors to their demise by appearing as an island on which they light a fire, only to be submerged when it dives.

8. Aboriginal Culture (Australia): In Aboriginal culture, sea turtles are considered totemic animals. They symbolize longevity, patience, and the connection between land and sea. Sea turtles are believed to carry the knowledge and wisdom of the ancestral spirits.

9. Chinese Culture: In Chinese folklore, the sea turtle represents longevity and wisdom. And it is considered one of the four celestial animals and is connected with the north and the element of water. The turtle is often depicted with a snake on its back, symbolizing the harmony between heaven and earth.

10. Mayan Culture: The ancient Mayans regarded sea turtles as sacred creatures associated with creation, fertility, and rebirth. They believed that the world was built on the back of a giant sea turtle. Mayans also saw sea turtles as messengers between the earthly and spiritual realms.

11. Maori Culture (New Zealand): In Maori, sea turtles, known as “honu moana,” are regarded as ancestral guardians. And affiliated with safe travels, protection, and a connection to the sea. Sea turtles also represent strength and perseverance.

12. Mediterranean Culture: Sea turtles symbolize good luck, protection, and the connection between humans and the sea in the Mediterranean region. They are often depicted in ancient Greek and Roman art and are seen as companions of seafarers.

Chapter 15

Importance of Sea Turtles to the Ecosystem

Sea turtles are vital contributors to the balance and well-being of marine ecosystems. As keystone species, they influence their environment and help regulate prey populations.

Also, their activities help maintain marine habitats, such as coral reefs and beaches. Let’s explore it further.

Grazing and Control of Prey

Sea turtles contribute to the control of prey populations. For instance, Leatherbacks help manage the population of jellyfish, which can have cascading effects on the ecosystem if left unchecked.

Habitat Maintenance and Creation

They also contribute to the maintenance of beaches and coastal vegetation. The nutrients left behind by turtle eggs and hatchlings that don’t survive provide valuable nutrients to the surrounding environment.

This process contributes to the stability and preservation of beaches and supports the overall coastal ecosystem. Turtle nesting also helps maintain beaches and contributes to a healthy marine environment.

Also, sea turtles contribute to the creation of habitats. When female sea turtles come ashore to nest, they dig nests in the sand, which helps aerate the beach ecosystem and provides important nutrients for the dunes and vegetation.

Food Source

Animals like birds, fish, and different mammals feed on sea turtles, especially the hatchlings. So, the presence of this marine provides nourishment and a food source to the ecosystem. Hence, they contribute to the overall balance and functioning of the food web.

Nutrient Cycling

When sea turtles migrate between feeding and nesting areas, they transport nutrients across different marine habitats. Their nutrient-rich waste acts as a fertilizer for seagrass beds and coral reefs, enhancing the productivity of these ecosystems.

Beach Erosion Prevention

As they dig nests and lay eggs on sandy beaches, sea turtles create pits and mounds that influence the sand distribution and promote a healthy beach profile. This helps to stabilize beaches and protect coastal areas from erosion.

Keystone Species

Sea turtles are considered keystone species, meaning they are an important part of their environment and influence other species around them. When a keystone species like a sea turtle is removed from a habitat, it can disrupt the natural order and impact other wildlife and fauna in different ways.

Coral Reef Health

Sea turtles help maintain the health of coral reef ecosystems. They assist in controlling the growth of certain organisms that compete with coral reefs for space. For instance, hawksbill turtles consume sponges, preventing them from overpowering coral reefs.

Chapter 16

Conservation Status of Sea Turtles

| Sea Turtle Species | IUCN Red List Status | United States ESA Status |

|---|---|---|

| Green Turtle | Endangered | Endangered: Florida and Pacific Coast of Mexico populations Threatened: All other populations |

| Loggerhead Turtle | Vulnerable | Endangered: NE Atlantic, Mediterranean, N Indian, N Pacific, and S Pacific populations Threatened: NW Atlantic, S Atlantic, SE Indo-Pacific, SW Indian populations |

| Kemp’s Ridley Turtle | Critically Endangered | Endangered: All populations |

| Olive Ridley Turtle | Vulnerable | Endangered: Pacific Coast of Mexico population Threatened: All other populations |

| Hawksbill Turtle | Critically Endangered | Endangered: All populations |

| Flatback Turtle | Data deficient (conservation status not determined) | N/A |

| Leatherback Turtle | Vulnerable | Endangered: All populations |

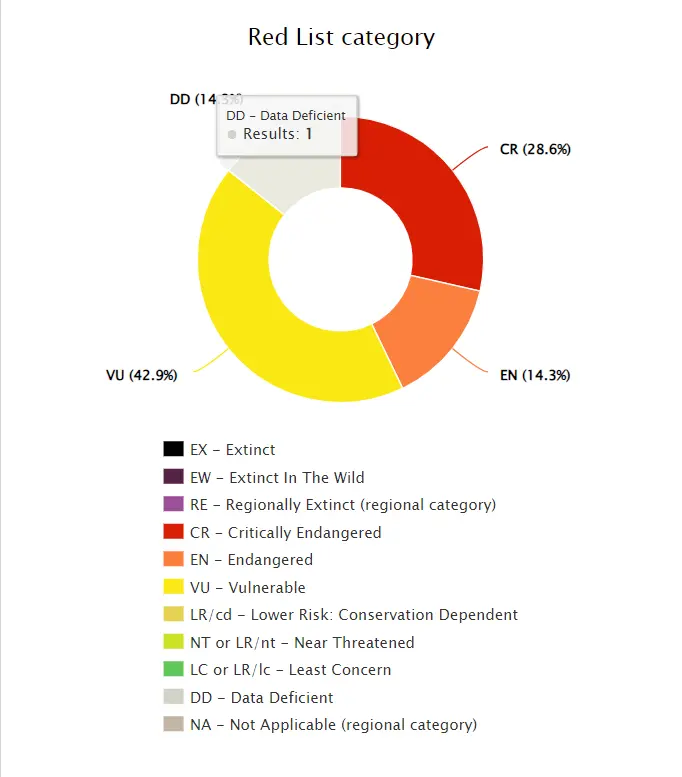

As we already mentioned, sea turtles worldwide have experienced a significant decline from their historical population levels.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species highlights the primary causes of this depletion, including persistent over-exploitation of adult females during nesting and the widespread collection of eggs, particularly impacting all six Caribbean sea turtle species.

The IUCN classifies Green sea turtles as “Endangered,” indicating a substantial decline of at least 50% over the last decade or three generations. Olive ridley, Loggerhead, and Leatherback sea turtles are classified as “Vulnerable.”

The situation is even more critical for Hawksbill, and Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles, classified as “Critically Endangered” on a global scale. This category is reserved for species that have experienced an alarming reduction of at least 80% over the past ten years or three generations.

And one species, Flatback, conservation status is unknown due to a lack of data.

The assessment process involves a rigorous and intricate process. Although it is carried out by a number of marine turtle specialists, part of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) within the IUCN, this is not immune to controversies.

For instance, a significant percentage of research on sea turtle foraging distribution has been conducted in regions classified as “least concern” by the IUCN.

And in the United States, all sea turtle populations occurring in U.S. waters are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The listing status of the loggerhead sea turtle in the U.S. is currently under review.

Chapter 17

What Can You Do to Help Sea Turtles?

As you have learned throughout the article, sea turtles are facing numerous threats to their survival. But do you know you can help these marine creatures to survive and create a better habitat for them? Yes, you can. And here are some ways you can help sea turtles:

Become a Conscious Seafood Consumer

When purchasing seafood, ask where and how it was caught. Choose seafood that is caught using methods that do not harm or kill turtles. You can consult sustainable seafood information networks to learn about the best choices.

Support Sea Turtle Conservation Efforts

Get involved with organizations and initiatives focused on sea turtle conservation. You can contribute through donations, volunteering, or participating in awareness campaigns and events.

You can also adopt a sea turtle. Through this, you will get a certification. And some organizations may let you name the turtle.

Report Sick or Injured Sea Turtles

If you come across a sick or injured sea turtle, contact your local sea turtle stranding network or relevant authorities. They can provide assistance and necessary care to the turtle. Also, don’t try to handle the sea turtle on your own.

Reduce Marine Debris

Take measures to reduce the amount of marine debris, as it can entangle or be mistakenly ingested by sea turtles. Participate in coastal clean-up activities and reduce your own plastic use to keep beaches and oceans clean.

Advocate for Turtle-Friendly Fishing Practices

Support efforts to eliminate sea turtle bycatch from fisheries. Encourage the use of turtle-friendly fishing hooks and the implementation of turtle excluder devices in nets. Promote sustainable fishing practices that minimize harm to sea turtles.

Help Combat Climate Change

Climate change affects sea turtles and their habitats. You can advocate for businesses and governments to reduce their emissions and take steps to mitigate climate change. Additionally, you can reduce your own carbon footprint through simple lifestyle changes.

Raise Awareness

Spread the word about the importance of sea turtle conservation. Educate others about the threats facing sea turtles, their ecological significance, and the actions individuals can take to protect them. By raising awareness, you can inspire more people to get involved and make a difference.

Reduce Beachfront Lighting

Bright lights on beaches can disorient sea turtle hatchlings, leading them away from the ocean and toward dangerous areas. If you live near a nesting beach, ensure outdoor lighting is sea turtle-friendly. Use low-intensity bulbs or shield lights to prevent unnecessary disorientation.

Chapter 18

7 Interesting Facts About Sea Turtles

Image Credits:

- Canva.com/photos

- ICUN

- seaturtlestatus.org

References and Information Sources:

- North Dakota Geological Survey. (2020, October 18). Archelon. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20201018221547/https://www.dmr.nd.gov/ndfossil/education/pdf/Archelon.pdf

- Sea Turtle Preservation Society. (n.d.). What Do Sea Turtles Eat? Retrieved from https://seaturtlespacecoast.org/what-do-sea-turtles-eat/

- Kot, C.Y., E. Fujioka, A. DiMatteo, A. Bandimere, B. Wallace, B. Hutchinson, J. Cleary, P. Halpin and R. Mast. 2023. The State of the World’s Sea Turtles Online Database: Data provided by the SWOT Team and hosted on OBIS-SEAMAP. Oceanic Society, IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group (MTSG), and Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab, Duke University. https://seamap.env.duke.edu/swot.

- Halpin, P.N., A.J. Read, E. Fujioka, B.D. Best, B. Donnelly, L.J. Hazen, C. Kot, K. Urian, E. LaBrecque, A. Dimatteo, J. Cleary, C. Good, L.B. Crowder, and K.D. Hyrenbach. 2009. OBIS-SEAMAP: The world data center for marine mammal, sea bird, and sea turtle distributions. Oceanography 22(2):104-115

- Senko, Jesse & Burgher, Kayla & Mancha-Cisneros, Maria & Godley, Brendan & Kinan‐Kelly, Irene & Fox, Trevor & Humber, Frances & Koch, Volker & Smith, Andrew & Wallace, Bryan. (2022). Global patterns of illegal marine turtle exploitation. Global Change Biology. 28. 10.1111/gcb.16378.

- Mazaris AD, Schofield G, Gkazinou C, Almpanidou V, Hays GC. Global sea turtle conservation successes. Sci Adv. 2017 Sep 20;3(9):e1600730. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600730. PMID: 28948215; PMCID: PMC5606703.

- Laloë, J., Cozens, J., Renom, B., Taxonera, A., & Hays, G. (2020). Conservation importance of previously undescribed abundance trends: Increase in loggerhead turtle numbers nesting on an Atlantic island. Oryx, 54(3), 315-322. doi:10.1017/S0030605318001497

- NOAA Fisheries. (n.d.). Sea Turtles. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/sea-turtles#by-species

- Casale, Paolo & Ceriani, Simona. (2019). Sea turtle populations are overestimated worldwide from remigration intervals: correction for bias. Endangered Species Research. 41. 10.3354/esr01019.